328 lines

22 KiB

Markdown

328 lines

22 KiB

Markdown

|

|

|

|||

|

|

A sudo vulnerability explanation guide.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The full video and walkthrough [here](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COHUWuLTbdk).

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

via [LiveOverflow](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/).

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

---

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# How Fuzzing with AFL works

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Table of contents

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

- [The Video](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#the-video)

|

|||

|

|

- [Introduction](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#introduction)

|

|||

|

|

- [AFL-gcc vs. LLVM](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#afl-gcc-vs-llvm)

|

|||

|

|

- [Fuzzer's Inner Workings](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#fuzzer-s-inner-workings)

|

|||

|

|

- [sudo vs. sudoedit](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#sudo-vs-sudoedit)

|

|||

|

|

- [Finally Fuzzing sudo](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#finally-fuzzing-sudo)

|

|||

|

|

- [Final Words](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#final-words)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Using LLVM and `clang`, we were able to fuzz Linux programs in the command line using the AFL fuzzer. Exploiting the fact that `sudoedit` is symlinked to `sudo`, we tried to find the CVE-2021-3156 vulnerability using fuzzing methods.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

## The Video[](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#the-video)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

## Introduction[](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#introduction)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

In the last article in the series, we talked about the critical `sudo` vulnerability (CVE-2021-3156) allowing an unprivileged user who is _not_ part of the `sudo` group to elevate their own privileges to `root`. We set up American Fuzzy Lop to fuzz function arguments in the terminal instead of using the program standard input. However, when we tried to run it, we hit a segmentation fault, and we're not sure why.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

It's important to consider that we are not following the method that the researchers used to find the vulnerability. Instead, we're choosing our own approach, relying on the actual documented methodology used by the researchers and others on the internet as a crutch when we run into some technical issues. This allows us to explore the context around this vulnerability in our own way, and in doing so, we _learn_. That is valuable.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

In today's article, we'll try to find a way around the segmentation fault that we encountered last time, so we can discover, analyze, and exploit the `sudo` vulnerability.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

## AFL-gcc vs. LLVM[](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#afl-gcc-vs-llvm)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

After the segmentation fault, we tried checking a few more things with `gdb`, to no avail. So we did what anyone else would do when they hit the proverbial wall: we googled it. Using `segmentation fault __afl_setup_first` as our query, we tried seeing if anyone else had had the issue. We didn't find anything conclusive; between `gdb` and our googling, we figured that it was time for a peek at what others had done in terms of fuzzing `sudo`.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Trying to find a solution online and exploring with `gdb`.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

We stumbled across a blog post by a certain `milek7` (available [here](https://milek7.pl/howlongsudofuzz/?ref=liveoverflow.com)) , titled "How long it would have taken to fuzz recent buffer overflow in sudo?". In this post, `milek7` sets out all the steps to follow in order to fuzz `sudo`, with a notable appearance of the `argv-fuzz-inl.h` header file and the `AFL_INIT_ARGV` function we've discussed in the previous article in this series. The _other_ important bit of information that `milek7` wrote is that

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

> For some reason afl-gcc instrumentation didn’t work, so I used LLVM-based one. We just need to override `CC` for `./configure`

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

which they followed up with this code snippet:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

CC=afl-clang-fast ./configure

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The blog post goes on to mention a few more things to do to get the fuzzing running successfully. But remember, we're trying to figure out most of it on our own and only rely on others' work when absolutely necessary... like when dealing with a mostly non-descript segmentation fault. So, we'll skip reading the rest and just focus on using the LLVM-based instrumentation.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

**An important note:** we could've avoided all of this by using `afl++`. We eventually will switch to it, but for now we're trying to make it work with `afl`. So why feature this in the video? It's important to us to be honest with you about the path we follow. Things are very rarely simple, straight lines between the start and the end of a project. There are often hiccups, detours, dead ends, going in circles... it's all part of it. For the sake of documenting our path and teaching you the lessons that we learned on the way, we'll stick to `afl` for now, and we'll change to `afl++` in due course.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

So, what's `clang`? Pronounced as "clang" or "c-lang", `clang` is a compiler front end for a number of different languages including `C` and `C++`. For its backend, `clang` uses the LLVM compiler infrastructure (LLVM is the name of the project, it is not an acronym). Its role is to act as a drop-in replacement for the GNU Compiler Collection, or `gcc`. We can use it to compile `afl` with the `argv-fuzz-inl.h` header file and modified main function in the `sudo.c` file.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The Wiki entry for `clang`.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The `afl` documentation has all the necessary information for using `clang` wrappers, and in turn, LLVM. We follow the instructions, using

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

CC=/path/to/afl/afl-clang-fast ./configure [...options...]

|

|||

|

|

make

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

to compile the code. In light of this change, we've included the `llvm` and `clang` packages in the Docker file so you don't have to do anything there. Check out our [GitHub page](https://github.com/LiveOverflow/pwnedit?ref=liveoverflow.com) for this article to get the code.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

When the compilation finishes, you can test and see if it works. Thankfully, this time it doesn't crash, and it even waits for your input.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Compiling...

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

No segfault, _and_ it even asks for your input!

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Just to refresh your memory since the last article and episode, the inclusion of the `argv-fuzz-inl.h` header file and the `AFL_INIT_ARGV()` function in `sudo.c`'s main function essentially takes what would be the standard program input `stdin` and creates a fake `argv[]` structure. This way, `afl` can fuzz programs' arguments in a shell.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Where we would normally type `sudo -l` for example, we now need to use `echo` to build a null byte-separated list of arguments that we can then pipe to `sudo`, like so:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

sudo -l

|

|||

|

|

echo -en "-l\x00" | ./src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

where `./src/sudo` is where our `sudo` binary is. The outputs are identical, showing that piping the list of arguments to `sudo` is just the same as calling it normally and appending the `-l` flag.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Piping `"-l\x00"` to `sudo`.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The binary should now be fuzzable with `afl`, then. Great! Let's create our input and output folders again. We can use the previous example as a test case.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

mkdir /tmp/in

|

|||

|

|

mkdir /tmp/out

|

|||

|

|

echo -en "-l\x00" > /tmp/in/1.testcase

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Let's fuzz! Run

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

afl-fuzz -i /tmp/in -o /tmp/out ./src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

`afl` now takes the test case we specified, sends it as an input to the `sudo` binary, and then fuzzes the data, trying to find interesting inputs.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

And we're fuzzing!

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

## Fuzzer's Inner Workings[](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#fuzzer-s-inner-workings)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

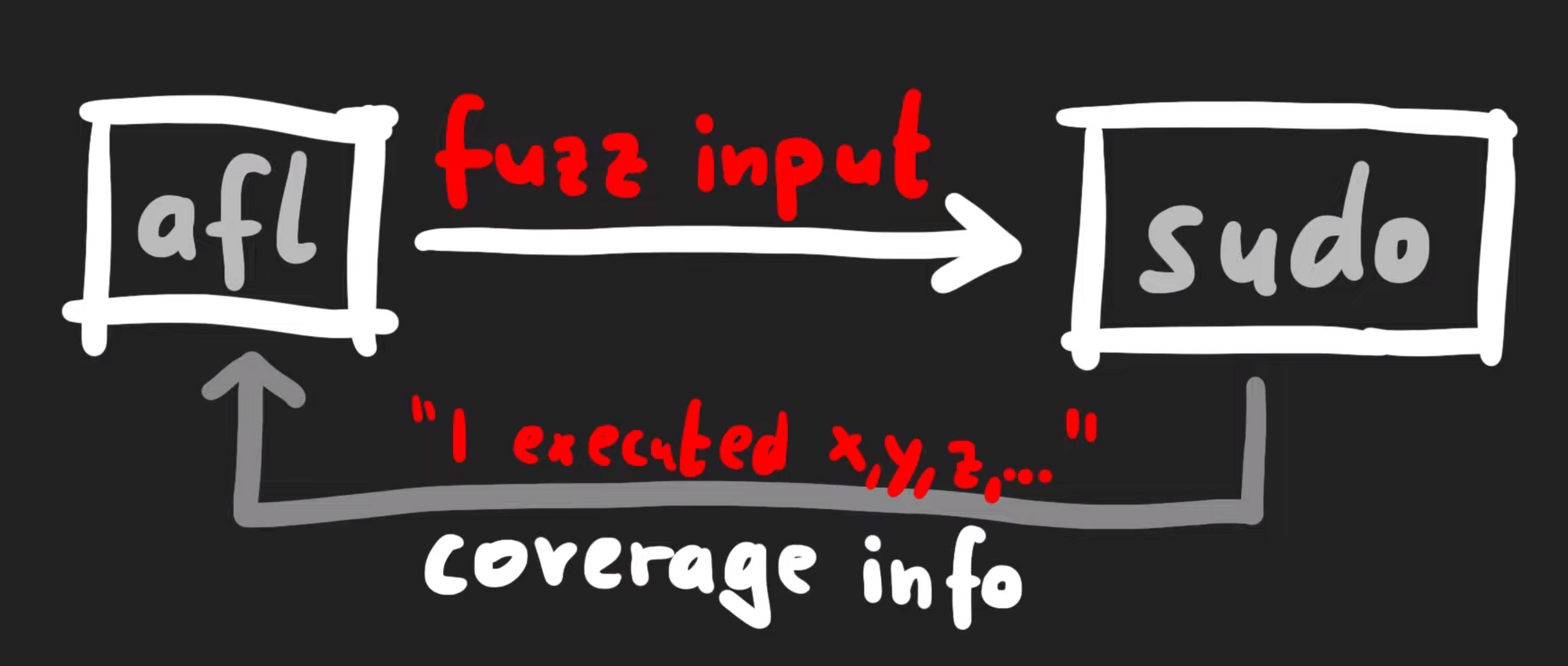

What does this really mean? `afl` is a guided fuzzer, which is why we had to compile `sudo` with the `afl` compiler as opposed to `gcc` like we would otherwise. It added small code snippets all over the place in the code in order to collect coverage information when executing. This is tantamount to `afl` throwing inputs at the `sudo` binary, and the binary reporting back what functions were executed. _That's_ coverage information.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Coverage information is about what was executed.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Technically-speaking, `afl` does not look at what functions were executed, but it's a simpler way to consider what's going on behind the scenes. There's actually a variety of different strategies when it comes to fuzzers collecting data to understand "coverage", but in general they involve monitoring a metric representing what code was executed versus what code was not. The different inputs are then compared. In `afl`'s case, it gathers data about edges.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

If you look at a binary in a disassembler such as `gdb`, you'll see the code can be represented as a number of basic blocks connected through those edges. In the case of `afl`, it's the same jump equal (or `je`), but at the destination of the branch, `afl` inserted a call to `__afl_maybe_log`, and the parameter to that call is a different value in each branch (`0x8136` versus `0xb1c3`). Therefore, when this instrumented code is executed, `afl` can log which branch is followed.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Code in a disassembler. The jump equal is identical, but at the destination, `__afl_maybe_log` is called with a different parameter in each branch.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

If most executions use the branch on the left, for instance, but all of a sudden a single execution uses the branch on the right, there is reason to further investigate this behavior. When `afl` is throwing inputs at `sudo`, the `sudo` binary instrumented with `afl` now collects information about the edges that were executed or visited. This information is returned to the `afl` fuzzer. `afl` can then mutate the input, use it with `sudo`, and evaluate whether this new input improved the coverage. From there, what is essentially a genetic algorithm is used to mutate inputs, discover new edges, and increase the coverage by evaluating which inputs give the same result, and preferring those that instead expand functionality coverage.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Now, let's come back to the big picture for a moment. Our input to `sudo` is basically a set of arguments, and the question is: can `afl` find the vulnerable arguments that result in the crash? If so, we expect `afl` to report a crash. With that in mind, go get a beverage of your choosing, sit back, relax, and stare at the `afl` screen while the fuzzer shuffles through titanic quantities of permutations in search of the set of arguments that'll throw `sudo` into a loop.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Will `afl` find a crash?

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

## sudo vs. sudoedit[](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#sudo-vs-sudoedit)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

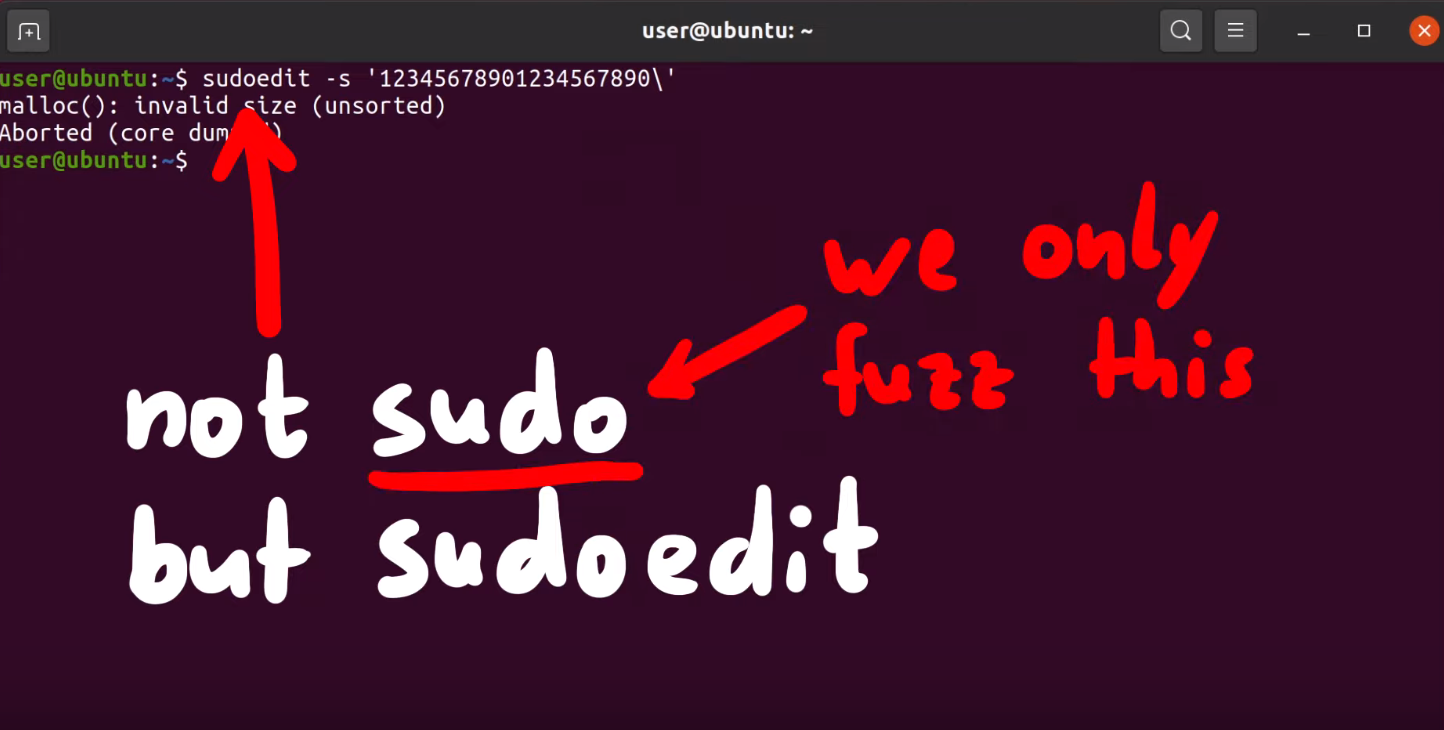

Alright, some of you are probably yelling at your screens right now. The CVE-2021-3156 vulnerability is using `sudoedit`, _not_ `sudo`. Why are we working with `sudo` then? How does that make any sense? Let us explain ourselves.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Are we even doing the right thing?

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

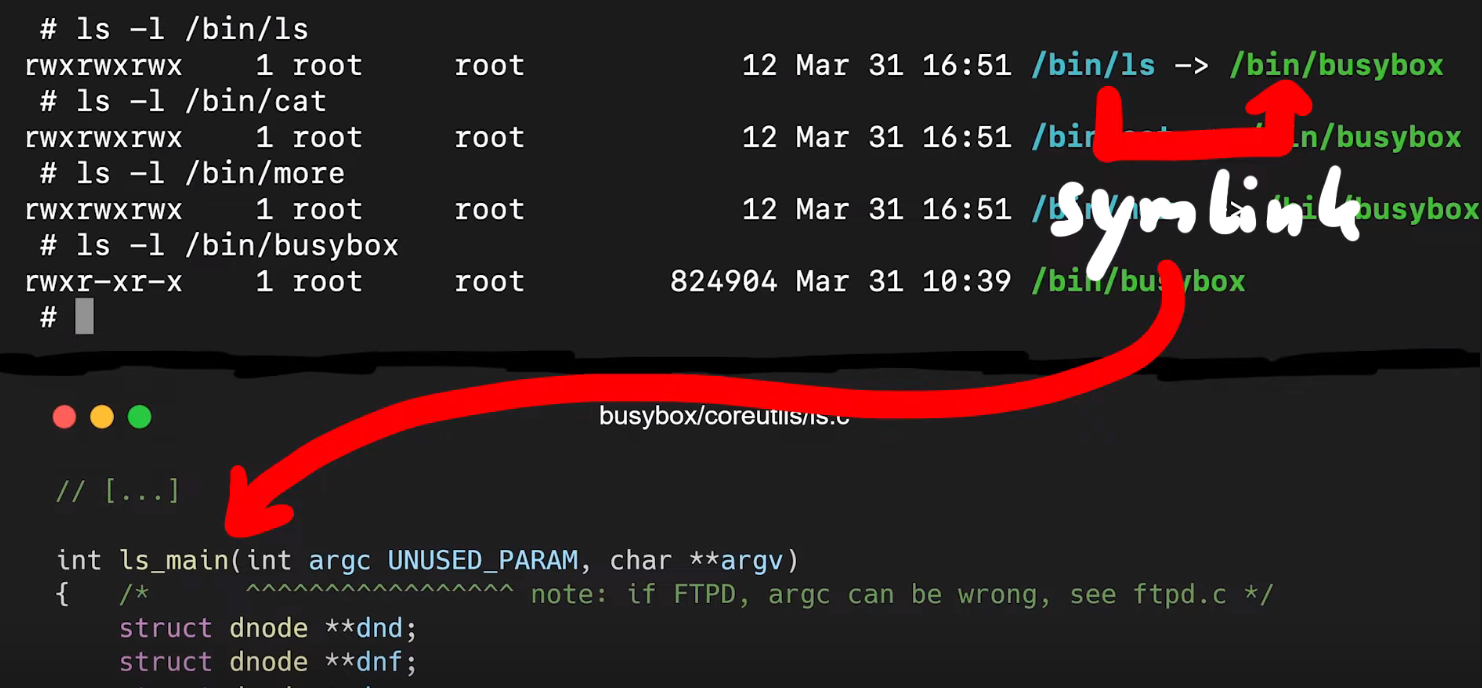

`sudoedit` is a symbolic link (or symlink, for short) to `sudo`. In the code for `sudo`, there is a check to see whether the utility was invoked as `sudo` or as `sudoedit`... or in fact _any_ name that ends in `edit`. Yes, that includes `pwnedit`. Nifty, isn't it? Right, so based on the name used to call the function, a different functionality of `sudo` is used.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

... yes, we are, because `sudoedit` is symlinked to `sudo`!

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Our `AFL_INIT_ARGV` wrapper function does not set `argv[0]`. Therefore, our fuzzer could never reach the vulnerable functionality from the `sudo` utility. This is a great example of a bad fuzzing harness. In this case, the code responsible for setting up and executing the target for fuzzing is missing crucial data that should be included in fuzzing. Don't worry, we'll fix it soon!

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

But before we do that, we wanted to take a little detour and discuss why `sudo` adopts a different functionality based on what way it is invoked in `argv[0]`. Have you ever heard about BusyBox? According to its [Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BusyBox?ref=liveoverflow.com) page,

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

> BusyBox is a software suite that provides several Unix utilities in a single executable file. It runs in a variety of POSIX environments such as Linux, Android, and FreeBSD, although many of the tools it provides are designed to work with interfaces provided by the Linux kernel. It was specifically created for embedded operating systems with very limited resources.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Here, "embedded operating systems" is really like the kind you'll find in IoT ("Internet of Things") devices. Now, `busybox` is a single binary, but it contains code from _tons_ of different packages and utilities including `addgroup`, `adduser`, `cd`, `mkdir`, `ls`, that kind of thing. If you look in `busybox`, you'll see that theses packages, `addgroup`, `adduser`, `cd`, `mkdir`, `ls`, are all symlinks back to the very same `busybox` binary.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

It's symlinks all the way down.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

So, let's have a quick peek into `busybox`'s actual code. Let's begin with `appletlib.c`, and specifically its `main` function. Like most any function, it receives `argv[]` arguments. If you scroll down through the code, you can see the `main` function takes `argv[0]` as the applet name, and then it runs the applet and then promptly exits. If you've ever done `C` programming, you might know that the arguments you use start at `argv[1]`, _not_ `argv[0]`, since that is usually the name and path of the binary. So, of course, you can write code that does something else based on what `argv[0]` is. When you execute the `ls` symlink on an embedded Linux distribution with `busybox`, it symlinks to the `busybox` binary but the `argv[0]` name will be `ls`, and thus the `ls_main` function will be executed.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

`ls` symlink on `busybox` executes the `ls_main` code.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

That's _also_ what `sudo` does with `sudoedit`. In fact, if you check for the location of `sudoedit`, you'll find that it is symlinked to `sudo`. That way, executing `sudo` and `sudoedit` will result in different things being displayed in the shell.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

With all this in mind, why fuzz `sudo` when the vulnerability is with `sudoedit`? It's because in our approach, we work as if we didn't know what the vulnerability was. So we don't know that we're supposed to fuzz `sudoedit`, we're just looking with `sudo` itself. This is however a great example of how having good Linux experience when starting research like this may pay off, as it may give you interesting paths to explore that others without Linux experience might not think about. With this kind of experience, you might think to have a look at the `sudo` manual page with

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

man sudo

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

which will mention `sudoedit` in the synopsis section of the `sudo` manual page. Or, perhaps you already knew that `sudoedit` is a symlink to `sudo`. In these cases, you'll know that `argv[0]` should be included in our fuzzing attempts. We decided to approach seeking out this vulnerability as if we didn't know about the symlinking or the value of `argv[0]`. In taking this approach, we could find out whether `afl` could find `sudoedit` through its genetic algorithm implementation, and therefore point us towards the vulnerability if we extend the `argv` fuzzing harness to include `argv[0]` instead of just `argv[1]`.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Due to `afl`'s genetic coverage-guided algorithm, `afl` can find valid complex file types. For instance, you can fuzz a `jpeg` parser, and `afl` will eventually find valid _images_ to test. Really cool, right? So maybe `afl` can find the `sudoedit` vulnerability if we allow it to fuzz `argv[0]`. Right now, it doesn't do that yet, because the `argv-fuzz-inl.h` header file specifies that

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```c

|

|||

|

|

int rc = 1; /* start after argv[0] */

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

C

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Remember, `rc` is the index of the fake `argv[0]` array, and it starts at 1. So, if we want to include the program invocation (and we do!), we just change that `1` to a `0`. Now you can compile this, but your test case will change. You have to specify the program name, too. So the

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

echo -en "sudo\x00" | ./src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

and

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

echo -en "sudoedit\x00" | ./src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

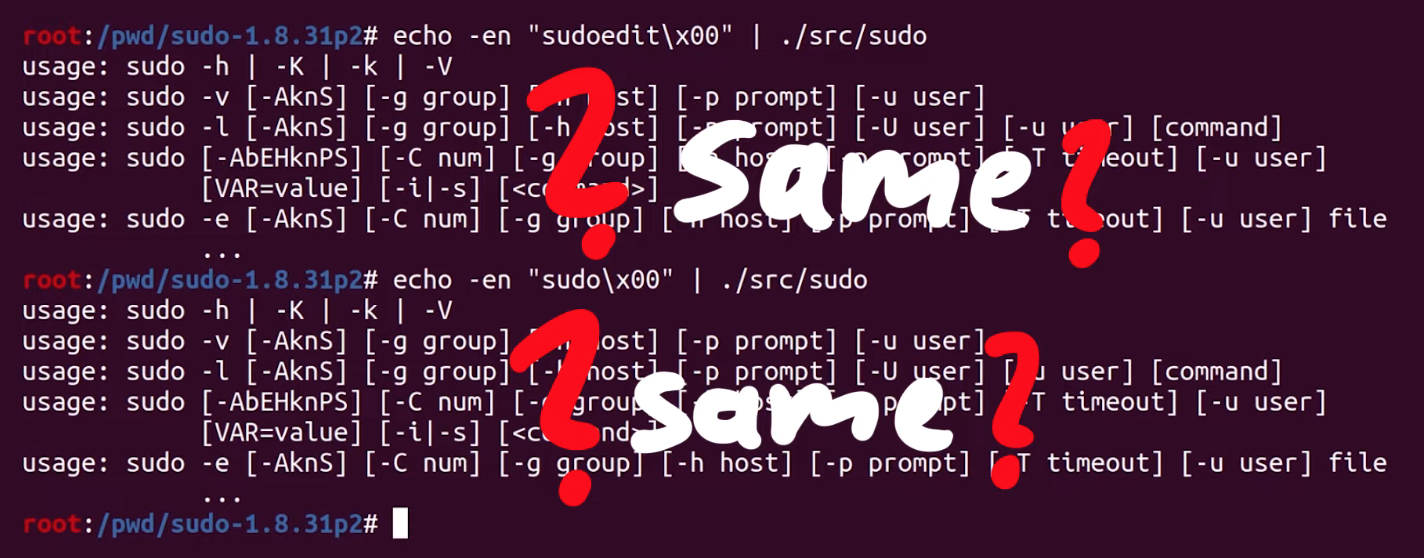

should have a different output, right?

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

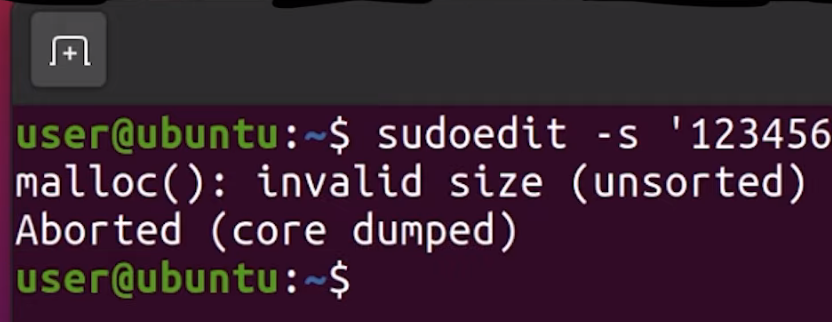

An unexpected result.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Unfortunately, they're the same. In both cases, we seem to execute `sudo`. We accidentally spoiled the solution for ourselves when we looked at `milek7`'s blog post earlier. We noticed that `milek7` mentioned

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

> Quick test shows that sudo/sudoedit selection doesn’t work correctly from testcases passed in stdin, because for some reason it uses `__progname`.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

... and not `argv[0]` to determine the program name. At the start of the `main` loop in `sudo.c`, there's a call to `initprogname`, and you can see that it passes `argv[0]`, and that this function `initprogname` is defined in `progname.c`. There, you can find that `sudo` checks if it has the `progname` function available at compile time, or if it has the compiler-specific `__progname` value. So, only if `progname` _and_ `__progname` don't exist will take the name from `argv[0]`. This means we need to modify the code. This one is simple: we can throw out the offending code so that the `argv[0]` name is _always_ taken. Let's compile the program again, and try. We test with

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

echo -en "sudo\x00" | ./src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

echo -en "sudoedit\x00" | ./src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

... and it works! Sweet!

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Throwing out the code that we don't need.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

## Finally Fuzzing sudo[](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#finally-fuzzing-sudo)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

So now, theoretically, `afl` should be able to find the `sudoedit` functionality and eventually find the vulnerability, too. So, we changed our test case to fuzz `sudo`, by writing in

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

echo -en "sudo\x00-l\x00" > /tmp/in/1.testcase

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

This time, we ran the fuzzer in parallel, with four different processes (hello, Amdahl's Law), which gave us a speed boost to find `sudoedit` _and_ the vulnerability. More details on the implementation are available on the `afl` GitHub [here](https://github.com/google/AFL/blob/master/docs/parallel_fuzzing.txt?ref=liveoverflow.com). We ran one fuzzer as the master one with the `-M` flag and the name right behind (`f1`), and then three children with the `-S` flag and the appropriate name right behind.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```bash

|

|||

|

|

afl-fuzz -i /tmp/in -o /tmp/out -M f1 /pwd/sudo-1.8.31p2/src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

afl-fuzz -i /tmp/in -o /tmp/out -S f2 /pwd/sudo-1.8.31p2/src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

afl-fuzz -i /tmp/in -o /tmp/out -S f3 /pwd/sudo-1.8.31p2/src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

afl-fuzz -i /tmp/in -o /tmp/out -S f4 /pwd/sudo-1.8.31p2/src/sudo

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bash

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

COPY

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

We want you to keep in mind though that our test case fuzzes `sudo`, _not_ `sudoedit`. Again, this is done on purpose, to see if `afl` can find `sudoedit` _and_ the vulnerability. _We_ think that it might not find it, but if it does, that it will take a _very_ long time. `afl` does a lot of bit flips, and a string like `sudoedit` is certainly multiple _bytes..._ but we'll see. This is the point of experimentation.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Time to parallelize.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Anyway, we got into our PJs, we poured ourselves a mug of our beverage of choice, sat back, relaxed, and watched those four lovely `afl` dashboards, realizing that there will be more technical hurdles to overcome in the very near future. Our advice to you? Get comfortable and get cozy.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

## Final Words[](https://liveoverflow.com/how-fuzzing-with-afl-works/#final-words)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

At the beginning of this article, we were facing a pesky segmentation fault that threatened the entire approach. After checking `milek7`'s resource online, we switched from the `afl-gcc` compiler to the LLVM one and managed to get around the segmentation fault. That's a victory!

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Once we got the fuzzer working, we considered _why_ we were fuzzing `sudo` instead of `sudoedit`. Once again, we are trying to find our own approach to the vulnerability. Using this method is consistent with what someone who did not know that the vulnerability was would do. Due to the symlink relationship between `sudo` and `sudoedit`, by fuzzing for the former with a wide enough scope, we should be able to find the latter, and hopefully, the vulnerability that goes with it. After changing the configuration in the `sudo` program to read `argv[0]` as the name of the program every time, we set up our test cases and got `afl` fuzzing.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

It's important to realize the progress we've made thus far - there's a lot! However, there will be some more technical challenges in the future that we'll need to overcome before we "uncover" the vulnerability. But we're well on the way. We'll pick up from here in the next article!

|